Marina Karem

Venice and the Jews: A Reflection in the Visual Arts

Summary

Dr. Marina Karem has started what appears to be a fruitful research on the treatment of Jewish figures in Venetian Art. The subject needed to be explored and, in her presentation at the conference, Dr. Karem outlined the preliminaries of her study. First, she would like to assess whether or not there existed a visual correspondence to the abundant literary documentation on Jewish-Venetian relations. In other words, does the representation of Jewish figures in Venetian painting match the demeaning restrictions reserved for them by the Venetian legal system? Secondly, she intends to compare and contrast the representation of Jewish figures between Venice and Northern Europe. The comparison is a necessary cultural foil against which we will be able to qualify more accurately the Venetians interaction with the Jewish community and its correspondence in the visual arts. Lastly, Dr. Karem wants to examine the depiction of Jews in the context of the so-called "Orientalizing mode." Contrary to the ideas of most modern scholars, Dr. Karem proposes that Venetian artists portrayed quite accurately the costumes of contemporary Jewish personages.

Dr. Marina Karem has started what appears to be a fruitful research on the treatment of Jewish figures in Venetian Art. The subject needed to be explored and, in her presentation at the conference, Dr. Karem outlined the preliminaries of her study. First, she would like to assess whether or not there existed a visual correspondence to the abundant literary documentation on Jewish-Venetian relations. In other words, does the representation of Jewish figures in Venetian painting match the demeaning restrictions reserved for them by the Venetian legal system? Secondly, she intends to compare and contrast the representation of Jewish figures between Venice and Northern Europe. The comparison is a necessary cultural foil against which we will be able to qualify more accurately the Venetians interaction with the Jewish community and its correspondence in the visual arts. Lastly, Dr. Karem wants to examine the depiction of Jews in the context of the so-called "Orientalizing mode." Contrary to the ideas of most modern scholars, Dr. Karem proposes that Venetian artists portrayed quite accurately the costumes of contemporary Jewish personages. Recently, on a trip to Greece, Dr. Karem found a 14th Crucifixion panel in the Museum of Byzantine Culture in Athens attributed to the circle of Paolo Veneziano. In the scene a Jewish figure is shown wearing a pointed red cap and turning his head away from the cross. This demonstrates that painters could be quite accurate in their portrayals of Jews. The panel also provides a glimpse of their attire in fourteenth-century Venice, a still obscure period. Later, in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, Dr. Karem plans to demonstrate that the regulations emitted by the Cattaver office regarding sumptuary rules were not observed as carefully.

View the complete paper -

Click to download:

Much has been published, particularly in recent times, on the subject of Venice and the Jews, from basic demographic studies to more complex analyses of the social, economic, cultural and religious interactions between the two communities. However, scholars such as Renata Segre and Benjamin Ravid, whose contributions in the field are well known, often warn about the risks in interpreting too literally what is left of the historical documents since the recorded events usually represent an exception to the rule rather than the norm. Artists, on the other hand, tend to interpret quite accurately the social mores of their own time and culture. An investigation of the visual records, therefore, would be a productive exercise which could give us a more precise and balanced account on the nature and status of the relationship between the Venetians and the Jews.

Interestingly, little has been done to study and catalogue the visual records. Only recently (1996) Heinz Schreckenberg published "The Jews in Christian Art." This chronologically-organized book is an exhaustive visual assessment of the relationship between the Jews and Western European Christians. However, not even one in the extensive collection of illustrations he published, relates to Venetian art. My study seeks to fill the gap by investigating the modes of representation of Jewish imagery in Venetian art. In this forum, my presentation is limited to the preliminaries of a thorough investigation to be completed in the near future.

My approach is three-fold: First, I assess whether or not there existed a visual correspondence to the abundant literary documentation on Jewish-Venetian relations. In other words, does the representation of Jewish figures in Venetian painting match the demeaning restrictions reserved for them by the Venetian legal system? Secondly, I compare and contrast the representation of Jewish figures between Venice and Northern Europe. The comparison is a necessary cultural foil against which we will be able to qualify more accurately the Venetians' interaction with the Jewish community and its correspondence in the visual arts. Lastly, I examine the depiction of Jews in the context of the so-called "Orientalizing mode." The trend of portraying Moslems, Eastern Jews as well as figures representing Christians living in the Orient wearing a turban of various shapes and colors is of much current interest. Besides Augusto Gentili's "Le Storie di Carpaccio: Venezia, I Turchi, gli Ebrei re-edited in 1996 and the contemporary article by Nabil Matar on the use of turbans in Renaissance England and in the East, this year's exhibition and the publication of the catalog "Venice and the Islamic World 827-1797" by the Metropolitan Museum in New York also address this issue. In older studies, the similarity in the costumes of Eastern figures depicted in Venetian art, be it Turks, Saracens, Jews or Christians, had prevented a proper identification of each group. The last phase of my work addresses the issue of accuracy in the portrayal of Eastern Jews in the Quattrocento and Cinquecento. In addition I examine whether or not the various sumptuary laws imposed on the Venetian Jews is reflected in the pictorial representations. My survey of the visual records focuses on the fourteenth through the end of the seventeenth century, since these dates include the earliest documentation on the Jewish presence in Venice until the events of the Counter Reformation, the activities of the Inquisition and its impact on the Jewish community.

The stereotypical representation of the Jews, with exaggerated noses, long beards, thin, grasping fingers and most notably, tall, pointed hats, ruelle (yellow circlets to be applied to the outer garments) and other distinguishing apparel, was already manifest throughout Europe by the end of the Fourth Lateran Council in 1215. Schreckenberg's encyclopedic collection of visual material could not be more specific. Almost invariably, from the period just after the Jewish War of 66-70 CE until the age of Enlightenment, Jewish imagery hroughout Western Europe, but more specifically in Germany and France, reflect strong anti-Semitic views. These representations varied in format and content; from portrayals of Ecclesia and Synagoga in which the personification of the Jewish religion was shown blindfolded and obstinately opposing the personification of Ecclesia, to grotesque caricatures in which Jewish figures were shown in obscene transactions with pigs. It is clear that, even if the collection of images gathered by Schreckenberg may represent as the author warns "the worst in Medieval Art," the circulation of this material, mostly in the form of affordable prints, reinforced and perpetuated the Christian cultural models which typically represented not simply a sense of "Otherness" or distinctiveness but a clear and blunt opposition towards Judaism.

Throughout Western Europe, the inimical approach adopted by Christians was undoubtably reinforced by the fact that Jewish personages shown in Christological events, the Passion in particular, were almost invariably depicted in contemporary clothing. Thus, the Jews' imputed responsibility for Christ's death was easily transferred to a contemporary setting. These images, then, had a constant and immediate appeal to contemporary society. In Germany (with few exceptions such as the work of Rembrandt in the seventeenth century), the perpetuation of the negative and corrosive propaganda imbued in the degrading representations, which, we must keep in mind, were available even to the poorest elements of society, must have contributed in setting the stage for the Jewish Holocaust. Indeed, for the culture of the Medieval and Early Modern periods, these images constituted the basic model of interpretation of the Jewish "Otherness."

The existing documentation on the cultural interchanges between Venetians and Jews indicates that in Venice the Jewish community was subjected to the same exclusion, opposition and debasement as in other parts of Europe. Yet, even a cursory examination of Venetian art demonstrates a clear dichotomy between an ever-changing but invariably unfavorable legislation towards the Jews and their portrayal in art. Indeed, the various laws promulgated to regulate the interaction between the Venetians and the Jews shows a strong interest on the part of the Venetians in maintaining a net separation between the two groups. On the other hand, in surveying the visual arts a different attitude emerges; an attitude of tolerance and respect truly at odds with what transpires in the historical documents. This is all the more surprising since the link between Venice and the North (which in the Medieval and Renaissance times included practically the whole of northwestern Europe) was historically a very strong one. Northern merchants, Germans in particular, constituted a formidable presence in Venice, especially during the Renaissance. And while their contribution to Venetian culture was largely economic in nature, they had ample opportunities to influence Venetian artists in their treatment of the Jews in art, particularly through their work in the printing business.

A case in point is the well-documented visits to Venice by Albrecht Dürer. Credited with having introduced the concepts of the Italian Renaissance to the Northern regions, the well-educated artist visited Venice in 1497 and again, for a longer sojourn, in 1506. After the second visit the artist shows significant changes in his style, both in the formal and coloristic approaches which he learned not only from

A case in point is the well-documented visits to Venice by Albrecht Dürer. Credited with having introduced the concepts of the Italian Renaissance to the Northern regions, the well-educated artist visited Venice in 1497 and again, for a longer sojourn, in 1506. After the second visit the artist shows significant changes in his style, both in the formal and coloristic approaches which he learned not only from Venetian artists such as Giovanni Bellini but also through the strong artistic legacy which Leonardo Da Vinci left in Venice. Leonardo believed that the virtue of a person was bound to be reflected in a harmonious and pleasant physiognomy. Likewise, an evil person would bear the marks of a brutish nature in grotesque facial features. Leonardo, who visited Venice in 1500 (and possibly at other times) left a strong impact on local artists, particularly in terms of compositional space, expressiveness and proportions. However, it was his fascination with the peculiarities of human nature, which he recorded in a multitude of drawings depicting "freakish" characters, which can be immediately recognized in the work of Dürer.

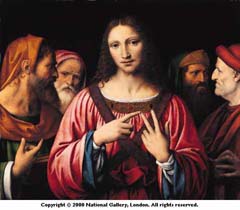

Venetian artists such as Giovanni Bellini but also through the strong artistic legacy which Leonardo Da Vinci left in Venice. Leonardo believed that the virtue of a person was bound to be reflected in a harmonious and pleasant physiognomy. Likewise, an evil person would bear the marks of a brutish nature in grotesque facial features. Leonardo, who visited Venice in 1500 (and possibly at other times) left a strong impact on local artists, particularly in terms of compositional space, expressiveness and proportions. However, it was his fascination with the peculiarities of human nature, which he recorded in a multitude of drawings depicting "freakish" characters, which can be immediately recognized in the work of Dürer.  Dürer's "Christ Among the Doctors" now in the Thyssen-Bornemisza collection in Madrid was painted while the artist was in Venice in 1506. The six Rabbinical scholars surrounding the youthful Christ, show a range of expressions varying from the sinister (in the upper left of the composition) to the cretin, most prominently displayed with his face almost touching Christ's. The inclusion of a "cretin" (the term was coined by Martin Kemp, one of the most reputable scholars of Leonardo) in the guise of a Jewish Rabbi arguing the fine points of Theology within the Temple, reveals the German artist's attitude towards the Jews more clearly than any documents. Thus, despite Dürer's professed admiration for Venetian culture and his attempts to acquire some of its sophistication (a point which he often discussed in his letters to his friend Willibald Pirckheimer in Nuremberg ) the artists' typically Northern views transpire in his demeaning characterization of the Jewish sages. Many Italian artists show Leonardo's influence.

Dürer's "Christ Among the Doctors" now in the Thyssen-Bornemisza collection in Madrid was painted while the artist was in Venice in 1506. The six Rabbinical scholars surrounding the youthful Christ, show a range of expressions varying from the sinister (in the upper left of the composition) to the cretin, most prominently displayed with his face almost touching Christ's. The inclusion of a "cretin" (the term was coined by Martin Kemp, one of the most reputable scholars of Leonardo) in the guise of a Jewish Rabbi arguing the fine points of Theology within the Temple, reveals the German artist's attitude towards the Jews more clearly than any documents. Thus, despite Dürer's professed admiration for Venetian culture and his attempts to acquire some of its sophistication (a point which he often discussed in his letters to his friend Willibald Pirckheimer in Nuremberg ) the artists' typically Northern views transpire in his demeaning characterization of the Jewish sages. Many Italian artists show Leonardo's influence.  The Lombard Bernardino Luini, for example, used one of Leonardo's caricature types for his "Christ Among the Doctors" painted in 1515. However, the same scene painted in the late 1530's by the Venetian Paris Bordone (now in the Isabella Steward Gardner Museum in Boston) shows a very different characterization.

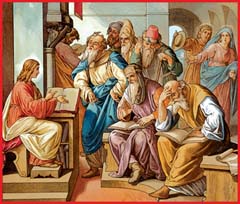

The Lombard Bernardino Luini, for example, used one of Leonardo's caricature types for his "Christ Among the Doctors" painted in 1515. However, the same scene painted in the late 1530's by the Venetian Paris Bordone (now in the Isabella Steward Gardner Museum in Boston) shows a very different characterization.  Christ is shown off-center, to the left of the composition. Most of the pictorial space here is given to the Jewish Doctors. Their individualized attitudes vary; from concentration (in the forefront figure) to disbelief (in the figure in the left background) to hard of hearing (the figure with the red hat). While the scene shows Christ as the typical adolescent boy with his parents (even a rarely shown young Joseph) entering the Temple and pointing proudly at their son, it is to be noted that Bordone avoids portraying the Doctors in the degrading manner used by Northern and even Italian artists (as we have seen in Luino).

Christ is shown off-center, to the left of the composition. Most of the pictorial space here is given to the Jewish Doctors. Their individualized attitudes vary; from concentration (in the forefront figure) to disbelief (in the figure in the left background) to hard of hearing (the figure with the red hat). While the scene shows Christ as the typical adolescent boy with his parents (even a rarely shown young Joseph) entering the Temple and pointing proudly at their son, it is to be noted that Bordone avoids portraying the Doctors in the degrading manner used by Northern and even Italian artists (as we have seen in Luino).

I use just another example: Hieronymous Bosch "Christ Carrying the Cross" executed in 1500, but the example can be multiplied over and over. Here Bosch has surrounded the cross-carrying Christ with sinister, malevolent characters, with multiple allusions to modern Jewry in the pointed head-gear worn by the various characters. A Venetian portrayal of the same scene,

I use just another example: Hieronymous Bosch "Christ Carrying the Cross" executed in 1500, but the example can be multiplied over and over. Here Bosch has surrounded the cross-carrying Christ with sinister, malevolent characters, with multiple allusions to modern Jewry in the pointed head-gear worn by the various characters. A Venetian portrayal of the same scene,  Titian's 1565 "Christ Carrying the Cross" now in the Prado Museumfocuses on the suffering of Christ, whose figure fills most of the compositional space. Significantly, the Venetian artist avoids blaming the Jews and introduces only the figure of "Simon the Cyrenian" as the Jew who, helped Christ in carrying the cross. It is evident, even at a glance, that when we compare the artistic treatment of key Christological themes, the Venetians, unlike Northern artists, do not reflect attitudes of animosity towards the Jews. And yet, we must note that the Venetians' contacts with Northern artists were more frequent and closer than in any other area in Italy.

Titian's 1565 "Christ Carrying the Cross" now in the Prado Museumfocuses on the suffering of Christ, whose figure fills most of the compositional space. Significantly, the Venetian artist avoids blaming the Jews and introduces only the figure of "Simon the Cyrenian" as the Jew who, helped Christ in carrying the cross. It is evident, even at a glance, that when we compare the artistic treatment of key Christological themes, the Venetians, unlike Northern artists, do not reflect attitudes of animosity towards the Jews. And yet, we must note that the Venetians' contacts with Northern artists were more frequent and closer than in any other area in Italy.

At the conclusion of his 1992 article "From Yellow to Red: On the Distinguishing Head-Covering of the Jews in Venice" Benjamin Ravid commented on the need for a thorough survey of Venetian art in order to better assess the degree of compliance among the Jews in Venice to the frequent and mutable sumptuary laws. These regulations seem to have preoccupied the Venetian authorities who had, in fact, established the Magistracy of the Cattaver precisely to supervise the enforcement of the various regulations. Ravid points out that while there is ample documentary evidence for the legislative changes regarding this issue, there are many indications that among the Venetian Jews, these laws were "made to be broken."

The survey of the visual records, which I am only beginning to entertain, would assess not only the degree of compliance to the law, but also provide us with a panoptic view of the Venetians towards this issue. Titian's 1539 "Presentation of the Virgin" executed for the Scuola Grande della Carita' for example, allows us a glimpse of that common attitude. While some members of the Scuola della Carita' (most probably portraits) are shown in the foreground, other attendants to the ceremony, to the right and left of the composition, were certainly meant to be the Jewish participants to the event. Notably, in this work, Titian portrayed the Jews as contemporary people. Benjamin Ravid, documents the denial of a request to wear a black baretta made by Jewish doctors to the Cattaver in 1529. Yet, in Titian's work there is no evidence of compliance to that restriction. If we take Titians' formal portrayal of the Jews as an example, it would seem that there was not only a "de facto" disregard of the official sumptuary laws, but that the Venetians generally accepted that disregard. As Titian's portrayal seems to indicate, the general population was not as concerned as the "Cattaver" about the Jews' compliance with the law.

The survey of the visual records, which I am only beginning to entertain, would assess not only the degree of compliance to the law, but also provide us with a panoptic view of the Venetians towards this issue. Titian's 1539 "Presentation of the Virgin" executed for the Scuola Grande della Carita' for example, allows us a glimpse of that common attitude. While some members of the Scuola della Carita' (most probably portraits) are shown in the foreground, other attendants to the ceremony, to the right and left of the composition, were certainly meant to be the Jewish participants to the event. Notably, in this work, Titian portrayed the Jews as contemporary people. Benjamin Ravid, documents the denial of a request to wear a black baretta made by Jewish doctors to the Cattaver in 1529. Yet, in Titian's work there is no evidence of compliance to that restriction. If we take Titians' formal portrayal of the Jews as an example, it would seem that there was not only a "de facto" disregard of the official sumptuary laws, but that the Venetians generally accepted that disregard. As Titian's portrayal seems to indicate, the general population was not as concerned as the "Cattaver" about the Jews' compliance with the law.

The last part of my research argues some of points made in recent publications which propose that Venetian artists such as Gentile Bellini and Giovanni Mansueti (as well as others) were simply expressing the exotic and colorful when portraying turbaned figures. According to scholars such as Julian Raby (who has recently contributed to the publication of the Catalog for the well-publicized Venice and the Orient exhibition) Venetian artists were not interested in accuracy when portraying the costumes of their various Oriental characters (which included Eastern or Levantine Jews). Rather, artists were believed to have elaborated or even invented new head-covers and ornamental details for their figures. I argue that, while artistic liberties might have been taken at times, for the most part Venetian artists reflected in their work both a knowledge of Venetian traditions and an interest in showing quite accurately the distinguishing attributes of Eastern Jews, Moslems (Turks and Saracens) or Eastern Christians. When completed, my research will offer not only a thematic survey of the portrayal of the Jews in the visual arts in Venice but, more importantly perhaps, a visual reflection of the contrast between the prescribed and actual attitudes between Venetians and Jews.

View the summary - Click to download:

Back to NEH Institute, July 2006