A Venetian Jewish Chronology

14th to 17th Centuries AD

This is my initial draft of a Venetian Jewish Chronology which eventually will come down to the present. The

initials at the end of entries (DR:3, etc) indicate sources, a list of which can be found at the end of the chronology.

I would appreciate any corrections, suggestions, additions, and whatnot you may have. Send them to Paul

Michelson pmichelson@huntington.edu. Thanks.

Table of Contents:

- The Fourteenth Century

- The Fifteenth Century

- The Sixteenth Century

- The Seventeenth Century

- Abbreviations/Sources

The Fourteenth Century

| 1314 | The first documented Jew in Venice is a man from Venetian Crete, bringing a petition to the Doge from the Jews of Crete. DR: 3 |

| 1338 -1339 |

Venice annexes Mestre and acquires a Jewish population. DR: 3-4 |

| 1382 | During the financial difficulties of the Fourth Genoese War (1378-1381), the Venetian government legalizes lending in Venice (which had been banned in 1254). All of those who accepted were Jews or associated with Jewish partners. DR: 3-4 |

| 1385 | In November, the Venetian Senate makes an agreement with Mestre moneylending Jews, the so-called Condotta (charter) allowing Jewish financial dealing in Venice. VG: 12; DR: 4 |

| 1386 | Venetian Senate decree grants the Jewish Community a cemetery on the Lido of 3,000 square meters. VG: 12, 90+ |

| 1387 | The Condotta is extended for ten years with some modifications. DR: 4 |

| 1388 | Venetian Senate forces Jewish moneylenders to lend to everyone (they had been unwilling to make smaller, less profitable loans). DR: 4-5 |

| 1394 | Venetian government declares that the Condotta will lapse in 1397 and Jews would no longer be allowed to live in Venice. DR: 4-5 |

| 1397 | Condotta lapses. Jews are not allowed to remain in Venice for more than 15 days at a time. Jewish men coming into the city were required to wear a yellow circle on their clothing to conform the decrees of the Fourth Lateran Council. DR: 5 |

The Fifteenth Century

| 1402 | Venetian Senate decrees that Jews had to have been out of Venice for four months before returning for another 15 days. DR: 5 | |

| 1408 | Senate exempts Jewish merchants from the Adriatic from these restrictions; they could come and go freely. The principle seemed to be to discourage Jewish moneylending, but encourage Jewish merchants and doctors and perhaps others from Terrafirma and the Venetian Stato da Mar. Most of the restrictions on Jews in Venice were not applied to Jews in the Venetian empire. DR: 5, 7 2 | |

| 1408 | Open practice of Judaism is prohibited. DR: 5 |  |

| 1424 | Venetian government prohibits sexual relations between Jewish men and Christian women. DR: 6 | |

| 1426 | Another law prohibits Jewish worship. DR: 5 | |

| 1437 | Birth of Isaac Abrabanel (1437-1508) in Lisbon, exiled from Spain in 1492, arrived in Venice in 1503 and promoted Portuguese-Venetian relations. He also wrote Docens Justitiam, a commentary on Maimonides Guide for the Perplexed, and a Commentary on the Pentateuch, which elaborated the myth of Venice from a metaphysical point of view and contributes to the Venetian legend. | |

| 1443 | Senate requires Jewish women as well as men to wear a colored badge. DR: 6 | |

| 1443 | Jews are prohibited from operating schools of games, crafts, doctrine, singing, or playing of instruments. DR: 6 | |

| 1443 | Penalties for sexual relations between Jewish men and Christian women are significantly increased. DR: 6 | |

| 1464 | On Jewish appeal to Pope Pius II's allowing of Jewish worship and threats of excommunication of those who prevented them from worshipping, the Ducal College allows Jews to meet and worship, but not establish synagogues or be in groups of larger than ten (the minimum in Jewish law for certain prayers and reading of the Pentateuch). DR: 5-6 | |

| 1492 | When Jews were expelled from Spain, rather few come directly to Venice. Later, they will come from the Ottoman Empire as Ponentine Jews. DR: 6 | |

| 1496 | Because of badge evasion, Venetian Senate requires Jews to wear a yellow hat (the baretta). The period between fifteen day stays in Venice is extended from four months to a year. DR: 6-7 | |

| 1497 | First Marrano law in Venice to deal with Spanish Jewish converts who secretly had remained Jews. They are to be expelled. (Jews in Spain had been forced to convert to Christianity in 1391 and in Portugal in 1497. These so-called "new Christians" were often suspected of false conversions. With the advent of the Spanish Inquisition in 1481 and the Portuguese Inquisition in 1536, many Marranos fled elsewhere.) DR: 7; ODWR: 619 | |

The Sixteenth Century

| Early 1500s | A noteworthy publishing house under Daniel Bomberg (who was not a Jew) is established, which published the Pentateuch, selections from the prophets, multiple editions of the Jewish Bible (1516-1517; 1524-1525, 1548), the Babylonian Talmud (1510-1523), the Palestinian Talmud (1522-1523), among other works. Of the nearly 4,000 Hebrew books printed in Europe before 1650, nearly a third were printed in Venice. VG: 14; GV: 80 ff.; DR: 169 ff. | |

| 1508 | War of the League of Cambrai leads to influx of Jewish refugees into Venice. DR: 7, VG: 12 |

|

| 1509 | Defeat of Agnadello leads to Franciscans blaming the Jews of Venice for Venice's problems. VG: 12 |

|

| 1513 | The Council of Ten signs a charter with Asher Meshullam of Mestre allowing him and his associates to lend money in Venice for five years. DR: 7-8 |

|

| 1515 | Jews are granted the right to sell secondhand goods (strazzaria) in nine stores. DR: 8 | |

| 1515 | A measure to restrict Jews in Venice to the Giudecca fails. DR: 8 | |

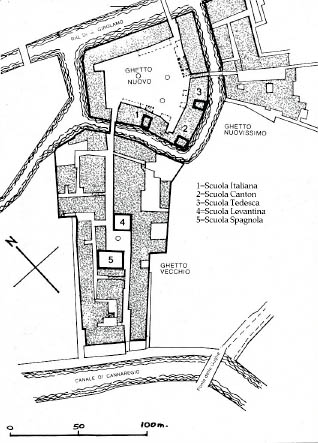

| 1516 | In March, Zaccaria Dolfin of the Collegio proposes that the Jews be confined to the Ghetto Nuovo island. Doge Leonardo Loredan agrees, and on 29 March a decree establishing the Jewish Ghetto is approved by the Senate. All Jews living in Venice are required to move to the Nuovo Ghetto, whose houses are to be evacuated at once. Jews are to pay one-third higher rent (Jews had been forbidden to own real estate in the fifteenth century). The two entrances to the Nuovo Ghetto are given gates which are to be closed between sunset and sunrise and the rest of the area is sealed off from quays and canals. It is also emphasized that no synagogues are allowed in Venice, even in the Nuovo Ghetto. The Nuovo Ghetto had been a dumping ground for the adjacent Ghetto Vecchio, Venice's copper foundry where bronze was also produced for artillery. The foundry had been closed down in 1434 when its functions were moved to the Arsenale and expanded. The Nuovo Ghetto was unusual in that it was one of the few Venetian campos that did not include a church; the island could thus be turned over to Jews without removing a religious structure. The Ghetto Nuovo was about 17 acres/7,000

sq. meters; 3,000 sq. meters were the campo. The population of the Ghetto in 1516 was 700 The term in Venetian Italian was originally "geto" or "getto". In 1541, "ghetto" came into usage. VG, 2005, 13 |

|

| 1518 | After extensive discussions in the Senate, the charter of 1513 is renewed for four years. DR: 10-11 | |

| 1523 | Charter is renewed again, but the Senate votes to set up a monte di pietà, a Catholic charitable pawnshop. This would have lessened the need for Jewish lending. DR: 11 | |

| 1524 | The Council of Ten orders the dropping of the monte project, for reasons unknown. Further discussion of a monte is prohibited. DR: 11 | |

| 1525 | Charter reconfirmed DR: 11 | |

| 1526 | In response to a proposed new tax, the Jews announce they would cease moneylending. The Senate in turn votes 105-95 to expel them. DR: 11 | |

| 1528 | Both sides back down and a new five year charter is established. DR: 11 | |

| 1528 | The Great German Scuola (Scuola Grande Tedesca) is founded in the Ashkenazi rite. The "German Nationals" were the first Jews to settle in the Ghetto and were composed of two groups: German Jews who had come to Italy in the 13th and 14th centuries and Italian Jews who had come from Rome and the south of Italy. VG: 30 | |

| 1531 | The Canton Scuola (Scuola Canton) is founded. They are also Ashkenazi, possibly from France. VG: 50 | |

| 1533 | Charter is renewed for five years. DR: 11 | |

| 1536 | The population of the Ghetto is 1,424. VG: 17 | |

| 1537 | Charter is renewed for ten years. DR: 11 | |

| 1538 | Elias Levitas publishes Massoreth ha-Massoreth (Tradition of Tradition). GV: 82 | |

| 1541 | The Jews from the Levant, the Levantine Jews, are granted the Ghetto Vecchio. A bridge, the Ponti degli Agnudi, is built over the Rio Ghetto. GUIDE: 80 84; VG: 13; DR: xiii |  |

| 1541 | The Levantine Scuola (Scuola Levantina) is founded. VG: 62 | |

| 1547 | The Venetian Inquisition is founded, but was subservient to the Venetian state, not the Papacy. The primary focus was on Protestantism, though Jews sometimes came under its purview. DR: 10 | |

| 1548 | Senate debates on the new charter, with one

proposal tabled to eliminate usury entirely. It

specifically permits the Jews to have synagogues. Eight synagogues were built in the Ghetto: three major synagogues in the Ghetto Nuovo (the Great German Scuola, the Canton Scuola, and the Italian Scuola) and three smaller ones (Scuola Coanim, Scuola Luzzato, and Scuola Meshullamin); and two in the Ghetto Vecchio (the Levantine Scuola and the Spanish or Ponentine Scuola). DR: 23 The 1548 charter became the model for the next 175 years of charters. DR: 12 |

|

| 1550 | Senate passes a law requiring Marranos to leave Venice and punishing Venetians who had dealings with them. Economic considerations keep these from being effectively applied and Marranos were not actively sought out. DR: 10 | |

| 1551 | The Collegio orders the Executors Against Blasphemy to examine Daniel Bomberg's Talmud. VG: 14 | |

| 1553 | Venice and the Papacy agree to publicly burn the Talmud and other Hebrew books, which was carried out in Piazza San Marco in late 1553. VG: 13; BR:25 | |

| 1555 | Counter Reformation Pope Paul IV picks up on the Venetian Ghetto idea and requires that in the Papal States, Jews should be restricted to a street or streets with a single entrance and exit. Rome's ghetto is so-called for the first time in 1562. LM: 281 | |

| 1556 | Counter Reformation Pope Paul IV cracks down on Marranos. Venice was not concerned with those who lived in the Ghetto. DR: 10 | |

| 1556 | New charter passes which made renewal automatic thereafter every five years. This ended the periodic bluffs and counterbluffs. It did mean that additional clauses could be added on renewal. DR: 12 | |

| 1558 | Renewal of the Charter is modified to prohibit Jews from employing Christian house servants. DR: 13 | |

| 1564 | Pope Pius IV authorizes republication of the Talmud, but censors it. VG: 14 | |

| 1566 | Joseph Nasi (aka Joao Micas, Giovanni Miches, and Juan Migues), a Marrano who had been banned from Venice in 1553, is appointed the Duke of Naxos by Sulieman the Magnificent's successor, Selim II. Nasi now conspired to settle scores with Venice and France. Venice is compelled to life his banishment and death sentence in 1567. He also tried gain control of Cyprus. This leads to Venice's loss of Cyprus and to the Battle of Lepanto in 1570. Nasi was also suspected of having a hand in the great Arsenale fire of 1569. GV: 90 ff. | |

| 1566 | The Executors Against Blasphemy order the destruction of thousands of Hebrew books, probably in reaction to the activities of the Duke of Naxos. GV: 85 | |

| 1571 | Following the loss of Cyprus and the subsequent Venetian triumph at the Battle of Lepanto, both in 1570, the charter comes under fire for nationalistic and religious reasons. The Jews are accused of supporting the Turks and seen as part of Joseph Nasi's schemes. The Senate, led by Alvise Grimani, votes to end the charter and expel the Jews by a 108 to 21 vote. They interpret Lepanto as a divine sign that Venice needed to be quit of Christ-deniers and traitors. The Jews have two years to get out. DR: 12; GV: 99 ff. | |

| 1571 | The Italian Scuola (Scuola Italiana) is founded for Jews of Roman origin, with slightly different practices from those of the German Ashkenazis. VG: 58 | |

| 1573 | As the two year grace period was expiring, the Avvogadori di Commun rules that the expulsion order is illegal, would raise the already banned monte di pietà issue, and the charter is eventually renewed. Venice's desire to establish good relations with the Ottoman Empire (which it did in 1573) may have been responsible for these reversals of field. Interestingly, these new ties with the Sultan were facilitated by Salomon Ashenazi, a Jewish doctor who had been in Venice and then Constantinople, who came to Venice in 1574 as Selim II's ambassador. Joseph Nasi's star waned with Lepanto; he died in Constantinople in 1579. DR: 12-13; GV: 101-105 | |

| 1573 | Venice actively tries to attract Jews to Venice. This was possibly part of a plan proposed by the Dalmatian Marrano Daniel Rodriga. DR: 10-11 |

|

| 1579 | Daniel Rodriga (a Marrano from Split in Dalmatia) proposes bringing to Venice fifty

Jewish merchant families in exchange for a 100 ducat payment each. He refers to these as "Ponentine Jews", i.e., Western Jews, to avoid Marrano, New Christian, or other red-flag terms. He also tried to change the Venetian status of Levantine Jews (whose rights were based on their status as Ottoman citizens). DR: 17; VG: 13; GV: 106 ff. |

|

| 1584 | The Spanish Scuola (Scuola Spagnola) is founded. VG: 52 | |

| 1588 | David de Pomis publishes De Medico Hebreo: Enarratio apologetica. De Pomis, one of the leading doctors of the day, was a avid promote of the Myth of Venice, emphasizing the similarities between the Laws of Moses and of Venice. Only a republic can resist tyranny (a thesis advanced previously be Isaac Abrabanel). In return, Venice not only disregarded Pope Pius V's forbidding of Jewish doctors (trained at the University of Padua, then the best medical school in Europe); it authorized de Pomis to practice medicine among Christians in 1593. Jewish doctors played a key role in Venetian public health, especially since their knowledge of Arabic gave them access to classical and Muslim sources. GV: 86 ff; DR: 25-26 | |

| 1589 | Cinque Savi approves a charter for the reception of the Ponentine Jews. They are also authorized to establish synagogues. The importance of Jews for the Venetian economy is demonstrated by the waving of the 25 year rule for becoming Venetians (something which had been in place since the 14th century). VG:13-14; DR: 18, 22 It was also specified that the Ponentine Jews could or even were expected to revert to

Judaism, flying in the face of the Counter Reformation. Paolo Sarpi defended the move

as for the greater good of Christian Europe (since without it the Jews might move with

their wealth to the Ottoman Empire). He also pointed out that the Pope had allowed

Marranos to function in Ancona. DR: 18-19 |

|

| 1591 | Number of Jewish pawnshops is set at three. DR: 13-14 | |

| 1597 | Charter renewal requires Jews to provide government with some furnishings from the strazzaria stores. DR: 13 | |

| 1597 | Shakespeare's Merchant of Venice is written and is influential in shaping stereotypes of Jews, though Shakespeare had no first hand knowledge of Venice (it was based on an already flourishing English "Myth of Venice") and the work contains many historical errors. DR: 26 | |

| 1599 | In the renewal charter of 1599, the Senate stated: "At this time, even greater are the reasons which on other occasions induced this Council to permit the residence of Levantine and Ponentine Jewish merchants in this city and their trade in the places of our state, principally for mercantile trade which is so important for the public service." DR: 19 | |

The Seventeenth Century

The great century of Venetian Jewish culture, including among others:Leon Modena (1571-1648)-a major Italian Jewish intellectual, rabbi, writer, preacher, musician, poet, teacher, and lecturer, who wrote a description of Jewish practices for King James I of England, Historia de' Riti Hebraici (History of Jewish Customs, published only in 1637), and an autobiography, Hayyei yehuda (The Life of Judah). GV: 152 ff.; LM: passim

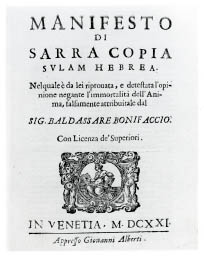

Sara Copio Sullam (1592-1641)-poet who hosted a literary

salon that included both Jews and non-Jews, men and

women. In 1621 she wrote a defense against charges in print

brought by Baldassare Bonifaccio, who had attended her

salon, that she did not believe in the immortality of the soul:

Manifesto di Sara Copio Sulam Hebrea nel quale è de lei riprovata

e detestata l'opinione negante l'immortalità dell'anima, falsamente attribuitale dal Signor

Baldassare Bonifaccio, de lei dedicato all memoria di Simon Copio suo dilettissimo genitore

(Manifesto by Sara Copio Sullam, Jewess, in which she condemns and deprecates the opinion

denying the immortality of the soul, falsely attributed to her by Signor Baldassare Bonifaccio,

dedicated to the Memory of Simon Coppio, her beloved father). GV: 173 ff.

Sara Copio Sullam (1592-1641)-poet who hosted a literary

salon that included both Jews and non-Jews, men and

women. In 1621 she wrote a defense against charges in print

brought by Baldassare Bonifaccio, who had attended her

salon, that she did not believe in the immortality of the soul:

Manifesto di Sara Copio Sulam Hebrea nel quale è de lei riprovata

e detestata l'opinione negante l'immortalità dell'anima, falsamente attribuitale dal Signor

Baldassare Bonifaccio, de lei dedicato all memoria di Simon Copio suo dilettissimo genitore

(Manifesto by Sara Copio Sullam, Jewess, in which she condemns and deprecates the opinion

denying the immortality of the soul, falsely attributed to her by Signor Baldassare Bonifaccio,

dedicated to the Memory of Simon Coppio, her beloved father). GV: 173 ff.

Simone Luzzatto (1583-1663)-Chief rabbi of Venice, author of the 1638 Discorso circa il statu de gl'Hebrei et in particolar dimoranti nell'inclita città di Venezia (Discussion on the State of the Jews and in particular the residents of the noble city of Venice), an interpretation of the myth of Venice which stressed the usefulness of the Jews commercially and otherwise (under 18 considerations) and their special bond with Venice. GV: pp. 179 ff.

Mosè Zacuto (1625-1692), the Jewish Dante and a Marrano, was the author of Tofteh Aruch (Hell Prepared, published only in 1715), discussing the fate of a person who doesn't think about life while alive and comes to think about human destiny only after death. He was also deeply involved in the Messiah Sabbatai episode, as the leading Kabbalist in Italy and a believer in the coming of a messiah. Kabbalah was a Jewish mystical movement that flourished in Venice in the late 1570s. Kabbalah was an esoteric competitor to Talmudism, focussing on knowing a God who both hides and reveals himself through contemplation and illumination. Its central text is the Zohar (Sefer ha- Zohar or Book of Splendour), a mystical commentary on the Pentateuch which probably appeared in Spain in the 13th century. Zacuto published in 1658 the Kabbalistic Zohar Hadash. GV: 211-212; p. 519, 1068-1069, 1063

During the 17th century, most of the Jewish schools are built, including the Scuola Luzzatto, Scuola Mesullanim, the Scuola Cohanim, and the Midrash Leon Modena. VG: 74

| 1630 | Plague hits Venice, leading to the death of some 50,000 of Venice's 150,000 population. VG: 17 |

| 1630 | The Senate is told that additional Jewish merchants would come to Venice is space were provided. The Senate responded by creating the Ghetto Nouvissimo. DR: 19 |

| 1633 | The Ghetto Nouvissimo is founded, mostly for wealthy merchant newcomers. VG: 14; DR: xiv |

| 1635 | Rebuilding of the Spanish Scuola is begun (completed in 1657) under the supervision of Baldassare Longhena. VG: 76-77 |

| 1645 | Veneto-Ottoman struggle for Candia (Crete) begins. This ends in 1699 with the Ottoman takeover of the island. Fifty years of conflict impoverished Venetian Jews, reduced their commercial role, and led to greater influence for messianic movements. The Jewish University paid vast sums into the Venetian treasury between 1669-1700. VG: 17-18 |

| 1650 | Population of the Ghetto was 4,000-5,000. The Jewish population of Venice was usually somewhere between 1 and 3% of the Venetian total. GUIDE:80; DR: 22 |

|

|

| 1665 | Sabbatai Zevi (1626-1676) of Smyrna is declared by Nathan of Gaza to be the Messiah and inspires a religious movement that persisted even after Sabbatai converts to Islam in 1666. Sabbatarianism had affinities to Kabbalah. GV: 212-213; ODWR: 881 |

| 1666 | Sabbatarian movement spreads to Venice, reopened the debate between lay Jewish community leaders and local rabbis. The rabbis (including Mosè Zacuto) were pleased by a rise in penitence, repentance, and religious zeal, but disturbed by the extremism (including attempts to abolish holidays and celebrations) of the followers of what they decided was a false messiah and false reports of miracles. They also feared that this could lead to Christian reprisals against Jews. There were heated meetings and debates, riots, and proclamations. This ended when news arrived of Sabbatai's conversion to Islam. GV: 213-215; ODWR: 881 |

| 1668 | Nathan of Gaza, Sabbatai's prophet, arrives in Venice, and is examined by the rabbis. They announce that he had failed the examination, a report signed by Nathan, who later repudiated his signature. Nathan is eventually discredited and the movement faded. Interestingly, Mosè Zacuto reportedly said Nathan's grasp of Kabbalah was much superior to his. GV: 215-217 |

| 1680 | The Levantine Scuola is rebuilt, probably under the supervision of Baldassare Longhena. GUIDE: 86 |

Abbreviations/Sources

| DR | Robert C. Davis and Benjamin Ravid, eds., The Jews of Early Modern Venice (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001). | |

| GV: | Riccardo Calimani, The Ghetto of Venice (New York: M. Evans, 1987). |  |

| LM: | Leon Modena, The Autobiography of a Seventeenth-Century Venetian Rabbi. Leon Modena's Life of Judah, translated and edited by Mark R. Cohen (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1988) | |

| ODWR: | John Bowker, ed., The Oxford Dictionary of World Religions (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997) | |

| TVG: | Roberta Curiel and Bernard Dov Copperman, The Venetian Ghetto (New York: Rizzoli, 1990) | |

| VE: | Francesa Brandes, ed., Venice and Environs. Jewish Itineraries, Places, History and Art (Venice: Marsiglio Editori, 1996) | |

| VG: | Riccardo Calimani, Anna-Very Sullam, and Davide Calimani, The Venetian Ghetto (Milan: Mondadori Electa, 2005). revised: vi 2007 | |

The Jews are not happy with this segregation, which may have been modeled on similar

special facilities for various national groups (the Fundaco dei Turchi, Fundaco dei

Tedeschi, the Greek Quarter, and of course, Venetian quarters in Constantinople and

elsewhere), and a few concessions were made, such as allowing Jewish doctors to leave

the Ghetto after hours. "The phenomenon of ghettoization was double-edged, however,

for though it severely restricted the physical freedom of the Jews, it did acknowledge

their legal right to reside in the city. Yet this right was not assured but only based on the

charter of 1513."1 DR: 8-10; VG: 12-13

The Jews are not happy with this segregation, which may have been modeled on similar

special facilities for various national groups (the Fundaco dei Turchi, Fundaco dei

Tedeschi, the Greek Quarter, and of course, Venetian quarters in Constantinople and

elsewhere), and a few concessions were made, such as allowing Jewish doctors to leave

the Ghetto after hours. "The phenomenon of ghettoization was double-edged, however,

for though it severely restricted the physical freedom of the Jews, it did acknowledge

their legal right to reside in the city. Yet this right was not assured but only based on the

charter of 1513."1 DR: 8-10; VG: 12-13