PORCELAIN

AND COCOA: THE PACIFIC RIM AND THE EARLY MODERN WORLD ECONOMY

In

1625, the English Dominican Friar Thomas Gage summed up the state of affairs in

Mexico City, commenting: “It is a

by-word that at Mexico four things are fair; that is to say the women, the

apparel, the horses, and the streets.”

Gages comments reflected several undeniable facts noticed by many

observers during the early seventeenth century. The silver boom experienced by both New Spain and Peru had

radically transformed Mexico City and Lima alongside other smaller cities and

towns. For almost one hundred years, the Spanish crown kept its colonies

relatively under its thumb. The

silver boom however, changed such a relationship. While these colonial cities diverted the wealth generated

from silver mines back to Europe, Gage couldn’t help but notice that much of

this wealth stayed in the Spanish colonies—particularly New Spain’s

capital, Mexico City. At the

capital, an emerging merchant class, increasingly economically independent of

Spain, began to develop a new sense of itself. While many merchants still held familial ties to the

peninsula, many others identified with Mexican—rather than

Spanish—interests.

In

his account, Gage also pointed out in amazement, “the beauty of some of the

coaches of the gentry [exceeds] in cost the best of the Court of Madrid and

other parts of Christendom, for they spare no silver…nor the best silks from

China to enrich them.” This

wealth, created indigenously and relatively free of direct Spanish control,

outstripped Spanish opulence (at least as Gage saw it) and expressed a

distinctive Asian influence. Thus,

Gage observed the display of a new merchant elite informed by the aesthetics of

not only the West—but also the East. As Gage further observed, traces of Chinese goods were

conspicuously displayed everywhere on the street:

Both

men and women are excessive in their apparel, using more silks than stuffs and

cloth. Precious stones and pearls

further much this vain ostentation.

A hat-band and rose made of diamonds in a gentleman’s hat is common, and

a hat-band of pearls is ordinary in a tradesman. Nay a blackamoor or tawny young maid and slave will make

hard shift, but will be in fashion with her neck-chain and bracelets of pearl

and her ear-bobs of some considerable jewels.

Gage

even observed the pervasive impacts of non-European styles and sensibilities

among fellow clergy, who drank “the Indian drink called chocolate” out of

Chinese porcelain cups. Thus,

Asian fashions, alongside New World products and wealth, helped create an

emerging American culture. In

fact, consumption was not only an elite affair, but by the early seventeenth

century permeated every social group in Mexico City. Within fifty years of the inauguration of the Manila Galleon

voyages, Mexico had inserted itself into the world economy. As Gage marveled, Mexican merchants,

priests, and slaves alike already tasted the global flavors yet to be fully

experienced by Europe. Although

officially a colonial arm of Spain, Mexico became one of the engines of the

early modern world economy—increasingly without Spanish financial and

military assistance.

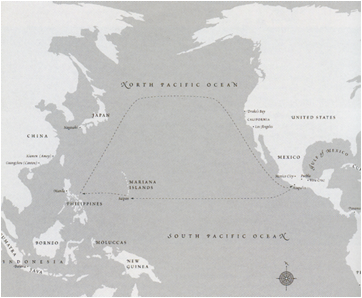

Image

1: Trade between China and Mexico

via the Manila galleons. Source:

George Kuwayama, Chinese Ceramics in

Colonial Mexico. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1997.

By

1625, Mexico City had become one of the richest cities in the world. Thanks to the establishment of silver

mines in Peru and Mexico, and direct trade route via Acapulco and Manila,

Mexican merchants quickly rose in power and wealth. As Asian goods like silk, porcelain, and tea, made their way

into the Atlantic World, they also infiltrated Mexican society. Most of these goods moved along

recently established roads emanating in all directions out of Mexico

City—such as the Camino del China and

El Camino Real. Both rare silks and porcelain moved

alongside domestically produced goods as far north as Santa Fe and south as

Guatemala.

Mexican

merchants also re-exported Asian goods to Peru and other points within the

Spanish colonial world. Peruvian

merchants sailed up to Acapulco and traveled overland to Mexico City over the

“China Road” to trade with Mexican merchants both crown-sanctioned and

contraband goods arriving from the China and the Philippines. Within this inter-regional American

network domestic and foreign goods crisscrossed along maritime and overland

routes. At the same time, Spanish

influence continued to assert itself.

European demand for Asian goods increased as silver, silks, and porcelain

made its way to Veracruz and into the Atlantic World. Within a decade, a complex series of global interconnections

rapidly solidified with each annual arrival of the Manila Galleon ported in

Acapulco.

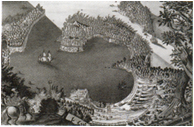

Image

2: Acapulco, 1613. Source: George

Kuwayama, Chinese Ceramics in Colonial

Mexico. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1997.

Mexican and Peruvian demand acted as a

“sink” for Asian producers equally hungry for New World silver. This vigorous Asian-American trade

couldn’t be fully monitored or controlled by Spanish or even imperial Chinese

authorities during the height of the first silver boom between the 1570s and

1630s. Indeed, Mexican merchants

and Chinese exporters engaged in a nascent free market trading network despite

the impositions and trading restrictions implemented by imperial and royal

authorities. The enormous influx

of new silver undermined traditional controls and restraints on the movement of

commodities.

This

unprecedented influx of wealth and exchange was clearly evident on the streets

of Mexico City in 1625. Far from a

peripheral region simply providing exports for Spain, Mexico City emerged as a

major player of the global trading network. By the seventeenth century, it

quickly transcended its role as merely a conduit of trade between Asia and

Europe. It became one of the global cities for a brief, shining

moment until the onset of the first silver bust at the end of the 1630s. During this period, Mexican merchants

began to formulate truly American identities. At the same time, distinct American artistic

forms—hybridizing Asian, Mediterranean, and New World styles—began

to flourish in centers like Mexico City and Puebla.

Perhaps

more than any other commodity, the production and consumption of Chinese porcelain

encapsulated new consumption/production patterns, as well as the creation of

new artistic and cultural traditions.

The porcelain trade clearly illustrates is. Other European traders like the Dutch and Portuguese engaged

in extensive porcelain trade with China (and even acted as middlemen

transporting Japanese and Mexican silver). Mexican traders, however, had silver and thus greatly

influenced the production of porcelain.

Scholars

Dennis O. Flynn and Arturo Giraldez have shown that Chinese demand for silver

ignited the world economy. Yet,

the “China craze” in New Spain and Peru also tugged on China’s economy as

well. The demands for silver and

porcelain (as well as silk) in Asia and North America fed each other. This frenzied trade loop continued

until the first silver bust in the New World and ousting of the Ming dynasty in

1644. Indeed, many historians have

made the link between the silver bust and Ming disintegration. Yet, none have looked at the Mexican

consumption side of the equation.

No study has revisited Gage’s observations that marveled at Mexico

City’s sense of itself and its place in the world. While silver production provides one aspect of Gage’s view

of Mexico, porcelain consumption provides another—perhaps even more

pervasive—part of the story.

Looking at the relationship between porcelain production and consumption

at its height between 1590-1630, this paper will highlight another crucial

piece of the early modern global economy.

While undertaking this social biography of porcelain, I will highlight

its production in Chinese centers like Jingdezhen, consumption by ambitious

Mexican merchants, and influence on emerging artistic traditions at cities like

Puebla. Throughout, I will

emphasize the central role of an autonomous—rather than

colonial—Mexico—in this emerging world economy.

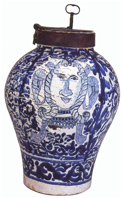

Image

3: Trading Routes in Early Modern

Mexico. Source: George Kuwayama, Chinese

Ceramics in Colonial Mexico. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1997.

THE

SOCIAL LIFE OF PORCELAIN

In

his study, “The Pilgrim Art: The

Culture of Porcelain in World History,” Robert Finlay highlights the global

dimension of porcelain. As he sees

it, the foundations of porcelain trade reach back millennia shortly after its

inception during the Yuan dynasty.

More importantly, Finlay argues that porcelain acted as the first true

manifestation of a global culture:

“porcelain and its imitations provide the first and most widespread

material evidence for sustained cultural encounters on an ecumenical scale,

perhaps even for intimations of truly global culture” (p. 187). Finlay traces not only European desires

for porcelain, but west Asian and Middle Eastern appeal as well. Yet, while Finlay covers the globe, he

fails to distinguish New Spain and Peru from Spain. Separating the desires and consumption patterns of the

colonies from the metropole supports Finlay’s argument while further

complicating the world historical picture.

Even

before Spain began to trade directly with China, though, porcelain production

situated itself within a vast international trading diaspora. The Jingdezhen region had long

dominated porcelain production since the Song dynasty. They owed their success, in part, to

the application of kaolin to their local aluminum oxide-deprived deposits of

china-stone—thus resulting in brilliant white porcelain pottery. By the Mongol period, Jingdezhen

potters produced bulk export porcelain for Middle Eastern markets more than

4,000 miles to the west. These

consumers demanded what would become a trademark style for the next three

hundred years—blue and white porcelain. Production expanded profitably over the next two

centuries. As demand increased

during the Ming period, Jingdezhen served as the largest industrial operation

in the world. Indeed, as European

demand increased the intensity of production by the sixteenth century,

porcelain accounted for 70,000 workers operating over 1,000 kilns. This assembly-line operation also

created small cities that housed employees. A later Qing account of a Jingdezhen porcelain factory

remarked at the growth of the town, “these rolls show that the town extends ten

‘li’ from north to south and ten from east to west. Its pottery business gives occupation to a thousand

houses. Its population is a

mixture drawn from all quarters of the compass, good and bad dwelling side by

side.”[1]

At

these massive industrial centers, blue and white porcelain—a style

frowned upon by Chinese domestic consumers but highly prized everywhere

else—became the primary export as well as most-produced commodity. Additionally, the types of ceramics

fulfilled the needs and wishes of outsiders—not the Chinese. Wine jars, utensils, large dishes,

basins, vases all catered to foreign markets.

While

foreign demand kept Jingdezhen operating, another foreign influx—

silver—helped to create a porcelain work force. The decision during the Ming to adopt a silver-based economy

dramatically re-shaped the Chinese and global market. Without the influx of New World silver, the expansion of the

porcelain industry might not have occurred. In other words, New World silver created mass-produced blue

and white porcelain, which fed the aesthetic demands of New World merchants,

artisans, and laborers alike. Not

only did Spanish policy and the Chinese silver sink determine the flow of

global trade, but Mexican consumption patterns and taste also influenced how

things unfolded.

PORCELAIN

AND MEXICO

Along

with the rest of the world, Mexicans greatly desired porcelain and “all things

Asian.” Asian products served

elite consumers. Uniquely situated

at the crossroads of international trade (especially of luxury goods) Mexican

merchants increasingly indulged in elite consumption. Mexico City, however, also served as the crossroads of major

domestic trading routes for both rare and bulk goods. All major commodities produced, raised, or consumed passed

through Mexico City. New World

crops, Old World livestock, and various preciosities from the hinterland (i.e.

turquoise) made its way to the city.

The

same held true for demographic numbers.

By 1634, over 58 percent of New Spain lived in and around the

capital. Thus, most of the

economic activity—both international and domestic—occurred in

Mexico City. A rising merchant class quickly emerged to orchestrate these

activities. The structure of

international commerce within the Pacific Rim particularly became the domain of

a small number of individuals.

During the early 1600s, only 246 merchants invested directly in the

Manila Galleon trade. In contrast

to the Atlantic trading network, these merchants held a more monopolistic grip

over the trade and maintained weaker ties with Spain.

These

merchants also engaged in extensive lending arrangements with local mining

agents and towns. At Manila and Acapulco,

merchants hired trusted allied port officials and inspectors to negotiate

according to the terms of Mexico City.

All of these efforts put merchants based out of Mexico City in frequent

opposition to Spain. The crown,

however, allowed them to continue because of the immense profitability of

silver mining and the Manila Galleon trade (known as the “Royal Fifth” of

silver). This tension continued

between royal action (which was undertaken in the case of Peru after 1582) and

inaction throughout the period.

Spain imposed restrictions on the number of Galleon voyages (two ships

of 300 tons per year after 1593) only to discover that illegal trade continued

while they lost out on the profits.

Additionally, Spain desperately tried to limit and eventually outlaw

trade between Mexico and Peru.

Like the Galleon trade, Madrid saw unchecked domestic trade as a

threat. The increasingly brisk

trade in Chinese goods further threatened Spain. Lima held an insatiable demand for luxury goods and cheaper

porcelain wares. Acapulco and

Mexico City expanded to meet the consumption demands of both colonies. Seville merchants, alarmed at their

quickly slipping trading monopoly, ultimately convinced the crown to prohibit

inter-colonial trade in 1631. The

Manila Galleon trade served somewhat as an economic addiction for Spain. Yet Mexicans merchants also

increasingly relied on the material goods flooding Mexico. As Mexicans increasingly donned silks

and other textiles, porcelain rapidly spread among both the elite and

commoners.

Image

4: Porcelain chards from Manila

Galeon. Source: George Kuwayama, Chinese Ceramics in Colonial Mexico. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1997.

The

types of porcelain pottery, peculiar by Chinese standards but nonetheless demanded

by Mexican merchants in Manila, filled several distinctly New World

tastes. First, since the Manila

route served as one of the longest voyages without portage in the world, water

and adequate supplies for the months long journey became a central concern. Thus, extremely large vessels used to

trap rainwater on the ship’s deck became one of the distinctive features of

exported Chinese porcelain. These

surviving giant-sized vessels serve as clear reminders of the importance of the

Manila trade. These vessels,

primarily obsolete and of little practical use, became ornaments for wealthy

merchants. Secondly, porcelain

served as ballast protecting silks and more perishable commodities on board the

Manila Galleons. Since large

amounts of porcelain also assisted in weighing down returning ships, it also

came over to Mexico in large quantities—and thus further stimulated

Chinese production. By 1574, one

galleon headed to Mexico contained an average of 22 thousand pieces of

porcelain (as compared to 700 pieces of silk and 500 marcos of gold). Within a decade, a Mexican “taste” for

porcelain grew alongside its newly discovered wealth and eating patterns. By the late 1500s, Mexicans regularly

engaged in a practice inherited from Aztec elites—drinking hot chocolate. Like Aztec aristocrats, Mexican elites

drank from coconut shells with silver mounts, called mancerina. As the

Manila trade became regularized, Chinese potters in Jingdezhen crafted

porcelain mancerinas to fit the

export niche demanded by Mexico.

Image

5: Mancerina. Source: George Kuwayama, Chinese Ceramics in Colonial Mexico. Honolulu:

University of Hawaii Press, 1997.

Mass

export production of Chinese porcelain expanded as long as silver continued to

flow. By the1640s, though, Mexican

silver mines exhausted themselves, and a global contraction occurred for

several decades until the next silver boom and explosion of sugar production

occurred. In the absence of

porcelain, artists and potters in ceramic centers like Puebla began to cater to

the elite tastes in Asian wares and styles. Puebla always served as a ceramic center since pre-contact

times. Situated nearby suitable

clay deposits and between Acapulco and Veracruz, Puebla potters quickly

incorporated Jingdezhen styles—such as transparent and white glazes and

overglaze enamels—into their domestic craft. While the Puebla pottery industry couldn’t compete with the

enormous wave of imported Chinese porcelain between 1590-1630, they quickly

filled the void left by the slowdown in the Manila trade. Previously, Puebla potters incorporated

indigenous Mexican styles with new technology and styles brought from Seville

(which were in itself Iberio-Islamic).

This style, known as majolica,

now incorporated Chinese techniques and styles. As a 1653 Puebla pottery guild regulation demanded: “In making the fine wares the coloring

should be in imitation of the Chinese ware, very blue, finished in the same

style and with relief work in blue, and on this style of pottery there should

be painted black dots and ground colors.”[2] Pueblan potters created their own version of the

Chinese porcelain cup, the pocillo,

for the consumption of hot chocolate.

Similarly, they created oversize tibors

that complemented the oversized vessels arriving from China in earlier

decades. Although Puebla potters

strove to incorporate Chinese porcelain influences into their ceramics, a

uniquely Mexican artistic tradition gradually coalesced as a continual stream

of Asian influences (and relative freedom from European artistic traditions)

made their way through Puebla on what became known as the “China Road.” As innumerable Mexican miners

sacrificed their lives to produce fabulous wealth for elites and Chinese

consumers, artists like the Puebla potters organized themselves as a skilled

workforce to generate new types of consumer goods. Thus, the push and pull of Chinese porcelain and New World

silver helped to create one of the most enduring artistic forms emerging in

Mexico—the ceramic tradition.

Image

6: Puebla tile of Mancinera and Cocoa tray. Source: Robin Gain, Donna Pierce, and Alfonso Pleguezuelo, Ceramicay Cultura: The Story of Spanish and Mexican Mayolica (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2003).

While

merchants and elites demanded niche items suited to particular tastes, blue and

white porcelain made its way into Mexico to fill the daily needs of its

citizens. Porcelain served as fine

ware and humble coins. Shattered

porcelain chards, accumulating on the ships of yearly Galleon voyages, proliferated

in the cities and countryside.

Called chinitas, these chards

acted as small coinage for daily transactions.

To understand the widespread usage of chinitas, it is important to highlight

Mexican trading routes, roads, and distribution centers associated with Chinese

porcelain. As mentioned above, all

routes, towns, and ports connected with Mexico City and therefore with

porcelain and the Manila trade. By

1600, the once-isolated and sleepy town of Acapulco periodically became a

boomtown with each arriving Galleon.

Chosen

for its deep harbor, Acapulco quickly became the only Manila Galleon

harbor. Acapulco, though, never

rose in power as a regional center.

The economic, cultural, and political tug of Mexico City proved too

great, and Acapulco merely swelled and retracted with the yearly galleons. While it didn’t achieve the greatness

of Mexico City, it did become the yearly destination for a motley gathering of

all classes of people. Once a

courier announced the arrival of an incoming ship, thousands of artisans,

merchants, and peddlers flooded the “China Road” connecting Mexico City with

Acapulco. All strata of

society—from king’s officials and soldiers to Indian hucksters and

muleteers—mingled on the road and in Acapulco. Along this road inns and hostels accommodated weary

travelers making their way along the 60-mile road. Next to Mexican pesos, chinitas

served as a common currency—especially along the “China Road.” Thus, the yearly arrival of the Manila

Galleons served as a cultural event that linked disparate segments of Mexican

society through the influx of Asian goods.

China

and Porcelain

Large porcelain

pottery factories sprouted up in Jingdezhen before increased Mexican and

European demand. However, the Latin American arrival in the Pacific marked a

new era of porcelain production.

At the palace factory, no less than twenty-three jobs associated with

porcelain manufacturing existed.

Not simply a small operation of artisan craftsmen, porcelain production

now entailed stampers, carvers, drawers, iron-workers, lacquerers, as well as

food preparers catering to the many employees at the factory. How-to manuals

for decorations as well as specialists associated with Kuan-Ku (official-old),

Shang-ku (superior-old), Ch’ang-ku (ordinary-old), foreign, and myriad other

porcelain styles provided guidelines for assembly-line production. Hundreds of types of wares could be

produced by request in accordance with illustrated catalogs. Silver and demand from Mexico and Peru

pushed much of this production, although with imperial controls firmly in place

over factories.

Image

7: Chocolate storage jar, Puebla,

17th century. Source:

Robin Gain, Donna Pierce, and Alfonso Pleguezuelo, Ceramicay Cultura: The

Story of Spanish and Mexican Mayolica (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2003).

The

silver boom, however, didn’t last.

Along with the Ming dynasty, porcelain producers in the Jingdezhen kilns

faced a potential crisis. By the

end of the sixteenth century, silver’s value began diminishing and the

stability of the Ming dynasty stood in doubt. The reign of the Wanli emperor (1573-1620) further evinced

rising corruption and imperial decadence.

Although Jingdezhen held a firm monopoly of the porcelain trade and

export production, the death of the emperor in 1620 marked the cessation of

imperial patronage of porcelain production. With the decline of silver value and royal funding, the

continued mass production of porcelain stood in doubt. Fortunately for the Jingdezhen region,

freedom from centralized control paved the way for widely diverse styles and

products.

No

longer restricted by strict controls on styles, and in need of steady patrons,

Jingdezhen potters and merchants began to work more closely with Dutch,

Japanese, and Portuguese traders.

Thus, the artistic styles of porcelain began to dramatically diverge

from earlier styles (although blue and white continued to thrive within the

Atlantic World). Known as the

transitional ceramic period (1620-1683), the porcelain of these chaotic times

stood at odds with earlier and later periods of production as completely new

technical forms emerged to meet the demands of the emerging world market.

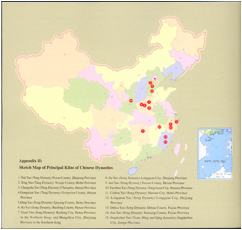

Image

: Porcelain Kilns in China. #15 includes the Jingdezhen kilns. Source: Li Zhiyan and Cheng Qinhua, Pottery and Porcelain (Beijing: Foreign Language Press, 2002).

As

China experienced decades of political and economic unrest, export porcelain

appeared to be “recession proof”—expanding in production to meet the

increasing demand of coffee, tea, and chocolate drinkers across the globe. The first real disruption of Jingdezhen

production, relatively unbroken since the eleventh century, didn’t occur until

the Manchus sacked the city and burned the kilns in the 1673. Although the establishment of the Qing

brought order to China and facilitated renewed patronage of porcelain

production, Europeans obtained the Chinese secret of porcelain production by

1708 and the earlier dynamic shared between New World silver and Chinese export

porcelain would never replicate itself again.

Chcocolate

Cup, Mexico City. Source: Robin

Gain, Donna Pierce, and Alfonso Pleguezuelo, Ceramicay Cultura: The

Story of Spanish and Mexican Mayolica (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2003).

The period between 1590-1630 served

as a unique moment that witnessed the birth of new cultural forms of expression

connected by the emergence of the first global culture. On either side of the Pacific, remarkable

parallels unfolded. In China,

porcelain production increasingly took on industrial characteristics as

factories expanded in size and complexity. Workers moved nearby, forming new neighborhoods plugged into

a new wage-earning economy.

Pegging itself to silver, the Ming dynasty made silver the currency used

to pay wages to porcelain producers.

At

the same time, Peruvian and Mexican silver mines also industrialized on an

unprecedented level. Silver mining

became increasingly mechanistic and efficient (the main difference between

porcelain and silver production, of course, lay in the vastly different working

experiences of the laborers). Like

porcelain production, new techniques (i.e. amalgamation) and technology became

institutionalized to assure the maximum effect. While miners didn’t necessarily benefit materially from

their labor, citizens of Mexico City and Lima certainly did. Silver exports ensured a wide array of

goods coming in from China. The

conspicuous consumption of Chinese porcelain became a Mexican pastime, not

necessarily a Spanish one since very little porcelain made it to Spain. While Mexico and China reconvened their

economic relationship via silver during the latter half of the seventeenth

century, the years between 1570-1630 marked a unique period of material and

cultural exchange. Indeed, while

silver initiated the first truly global economy, porcelain forged the earliest

inclinations of both a New World identity and a larger global culture.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Axel, Jan and

Karen McCready. Porcelain: Traditions and New Visions. New York:

Watson-Guptill Publications, 1981.

Ayers, John and

Rose Kerr. Blanc de Chine: Porcelain

from Dehua. Richmond,

Surrey: Curzon Press, 2002

Borah,

Woodrow. Early Colonial Trade and Navigation Between Mexico and Peru. Berkeley: University of California, 1954.

Butler, Sir

Michael, Stephen Little and Margaret Medley. Seventeenth Century

Chinese Porcelain from the Butler Family Collection. Alexandria, VA:

Art Services International, 1990.

Butler, Michael,

Stephen Little and Julia Curtis. Shunzhi Porcelain: Treasures from an Unknown Reign, 1644-1661. Seattle and London: University of Washington Press, 2002

Carswell,

John. Blue and White: Chinese

Porcelain Around the World. London: British Museum Press, 2000.

Chen, Jennifer,

Julie Emerson, and Mimi Gardner Gates.

Porcelain Stories: From China to Europe. Seattle: University of Washington, 2000.

Curtis, Julia

B. Chinese Porcelains of the Seventeenth Century: Landscapes, Scholars’ Motifs and

Narratives. Seattle and

London: University of Washington

Press, 1995.

Eberlein, Harold

Donaldson and Roger Wearne Ramsdell.

The Practical Book of

Chinaware. Philadelphia and

New York: J.B. Lippincott Company,

1948.

Finlay,

Robert. “The Pilgrim Art: The Culture of Porcelain in World

History,” Journal of World History 9,

2(1998), p. 141-187.

Fisher, John

R. The Economic Aspects of Spanish Imperialism in America, 1492-1810. Liverpool: University of Liverpool Press, 1997.

Flynn, Dennis O.

and Arturo Giraldez. “Cycles of

Silver: Global Economic Unity

through the Mid-Eighteenth Century,” Journal

of World History 13, 2(2002), p. 391-427.

Frelinghuysen,

Alice Cooney. American Porcelain, 1770-1920.

New York: Metropolitan

Museum of Art, 1989.

Hoberman, Louisa

Schell. Mexico’s Merchant Elite, 1590-1660: Silver, State, and Society. Durham:

Duke University Press, 1991.

Hobhouse,

Henry. Seeds of Change: Five

Plants that Transformed Mankind (New York: Harper and Row, 1986.

Impey, Oliver. The

Early Porcelain Kilns of Japan:

Arita in the First Half of the Seventeenth Century. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1996.

Jenyns,

Soame. Later Chinese Porcelain:

The Ch’ing Dynasty (1644-1912).

New York: Thomas

Yoseloff, 1965.

Jenyns,

Soame. Ming Pottery and Porcelain.

London: Faber and

Faber, 1988.

Kuwayama,

George. Chinese Ceramics in Colonial Mexico. Honolulu:

University of Hawaii Press, 1997.

Little,

Stephen. Chinese Ceramics of the Transitional Period: 1620-1683. New

York: China Institute in America,

1984.

Lopez, Carmen

Yuste. El Comerico de la Nueva Espana con Filipinas, 1590-1785. Mexico City: Instituto de Nacional de Antropologia e

Historia, 1984.

Macintosh,

David. Chinese Blue and White Porcelain.

London: Bamboo Publishing,

1986.

Mantecon,

Matilde Souto. Mar Abierto: La Politica y el Comercio del Consulado de Veracruz en el

Ocaso del Sistema Imperial. Mexico

City: El Colegio de Mexico, 2001.

Mudge, Jean

McClure. Chinese Export Porcelain in North America. New York:

Crown Publishers, 1986.

Pope, John

Alexander. Chinese Porcelains From the Ardebil Shrine. Washington, D.C.:

Smithsonian Institution, 1956.

Sayer, Geoffrey

R. Ching-Te-Chen: Tao-Lu, or

the Potteries of China. London: Routledge, 1951.

Scheurleer, D.F.

Lunsingh. Chinese Export Porcelain:

Chine de Commande. New

York: Ptiman Publishing

Corporation, 1974.

Schurz, William

Lytle. The Manila Galleon. New

York: E.P. Dutton, 1959.

Scott, Rosemary

E. Elegant Form and Harmonious Decoration: Four Dynasties of Jingdezhen Porcelain. London: Sun Tree Publishing, 1992.

Souza, George

Bryan. The Survival of Empire:

Portuguese Trade and Society in China and the South China Sea,

1630-1754. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986.

Spero, Simon. The

Bowles Collection of 18th Century English and French Porcelain. San Francisco: Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco,

1995.

Stein, Barbara

H. and Stanley J. Stein. Silver, Trade, and War: Spain and America in the Making of

Early Modern Europe. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 2000.

Thompson, J.

Eric S. (ed). Thomas Gage’s Travels in the New World. Norman:

University of Oklahoma Press, 1958.

Vainker,

S.J. Chinese Pottery and Porcelain:

From Prehistory to the Present.

London: British Museum

Press, 1991.

Wen, Cheng and

Li Zhiyan. Chinese Pottery and Porcelain.

Beijing: Foreign

Language Press, 1984.

Warren, David

B. “The Arts of Viceregal Mexico,

1521-1821: A Confluence of

Cultures,” Magazine Antiques April

2002.

Wilson, Philip. Chinese

Export Porcelain: From the Museum

of Anastacio Goncalves, Lisbon. London: Philip Wilson Publishers, 1996.