Prized for

their warmth, luxurious texture, and the longevity of

fur as a

material, furs have

played a large role in clothing

people since the beginning of human history. For everyday

use or costume and decoration, furs have been used for the

production of outterware

such as coats and cape, garment and shoe lining, a

variety of head coverings, and ornamental trim and

trappings.

Prized for

their warmth, luxurious texture, and the longevity of

fur as a

material, furs have

played a large role in clothing

people since the beginning of human history. For everyday

use or costume and decoration, furs have been used for the

production of outterware

such as coats and cape, garment and shoe lining, a

variety of head coverings, and ornamental trim and

trappings.  removed, and felts (removing the fur from the pelt, and

processing it with heat and pressure to form

a piece of pliable material). Due to the strength

and malleable quality of felts, they were used extensively in hat

making. The physical structure of beaver fur predisposes it to

the felting process, making it a highly desirable fur for felt

production. (photo of beaver fur hat courtesy of www.chichensterinc.com/FurHats.htm)

removed, and felts (removing the fur from the pelt, and

processing it with heat and pressure to form

a piece of pliable material). Due to the strength

and malleable quality of felts, they were used extensively in hat

making. The physical structure of beaver fur predisposes it to

the felting process, making it a highly desirable fur for felt

production. (photo of beaver fur hat courtesy of www.chichensterinc.com/FurHats.htm) felts.

The careful guarding of

this trade secret helped to maintain the Russian monopoly.

(photo of felted beaver hat courtesy of www.pilgrimhall.org)

felts.

The careful guarding of

this trade secret helped to maintain the Russian monopoly.

(photo of felted beaver hat courtesy of www.pilgrimhall.org) Fortunately, although perhaps not for the American beaver,

the

depletion of European beaver populations coincided with the

establishment of European colonies in North

America.

England, France, and the Netherlands had all established

North American colonies by the early-to-mid 17th

century. Although beaver populations could be found

all over

North America, beaver in the northern parts of the

continent

contained the fuller coats that were more desirable in the fur

trade.

As a result, French Canada, British holdings in the Hudson Bay, and the

Dutch New Netherlands (later, the English colony of New York) played

key roles in establishing the North American fur trade.

Because there were no

physical differences between the north American beaver (Castor canadensis) and the European

beaver (Castor fiber), the

American beaver was an easy substitute for the

near-extinct European beaver. (image courtesy of www.iroquoisdemocracy.pdx.edu)

Fortunately, although perhaps not for the American beaver,

the

depletion of European beaver populations coincided with the

establishment of European colonies in North

America.

England, France, and the Netherlands had all established

North American colonies by the early-to-mid 17th

century. Although beaver populations could be found

all over

North America, beaver in the northern parts of the

continent

contained the fuller coats that were more desirable in the fur

trade.

As a result, French Canada, British holdings in the Hudson Bay, and the

Dutch New Netherlands (later, the English colony of New York) played

key roles in establishing the North American fur trade.

Because there were no

physical differences between the north American beaver (Castor canadensis) and the European

beaver (Castor fiber), the

American beaver was an easy substitute for the

near-extinct European beaver. (image courtesy of www.iroquoisdemocracy.pdx.edu) The

exchange of goods inhabited a realm that tied two cultures together

economically, symbolically and politically. An open market for

European goods in the colonies, and the supply of raw material from the

colonies to Europe, helped drive the colonial economy. The

introduction of steel tools and gun powder weaponry transformed

indigenous American society. The Europeans, on the other hand,

heavily relied upon their Native American neighbors for access to

American resources, such as the beaver. (image courtesy of www.lcmm.org/site/harbor/resource_pages/timeline/contact/exploration.htm)

The

exchange of goods inhabited a realm that tied two cultures together

economically, symbolically and politically. An open market for

European goods in the colonies, and the supply of raw material from the

colonies to Europe, helped drive the colonial economy. The

introduction of steel tools and gun powder weaponry transformed

indigenous American society. The Europeans, on the other hand,

heavily relied upon their Native American neighbors for access to

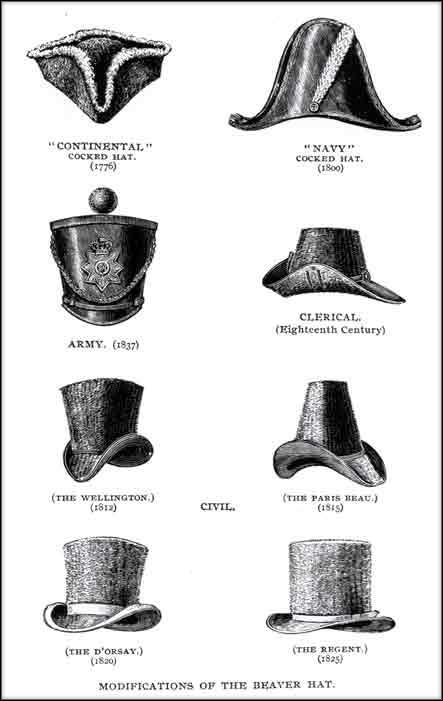

American resources, such as the beaver. (image courtesy of www.lcmm.org/site/harbor/resource_pages/timeline/contact/exploration.htm) shape,

and material all carried specific

meaning. In Ecclesiastical heraldry, for

example,

a red, wide-brimmed hat clearly indicated that its

wearer was a cardinal, and

interactions required a specific social protocol. In

seventeenth

century England, the shape and style of one's hat

reflected

political and religious affiliation. Due to the

expense of a

beaver hat, being able to purchase one made a visual statement

about

one's wealth and social status.

shape,

and material all carried specific

meaning. In Ecclesiastical heraldry, for

example,

a red, wide-brimmed hat clearly indicated that its

wearer was a cardinal, and

interactions required a specific social protocol. In

seventeenth

century England, the shape and style of one's hat

reflected

political and religious affiliation. Due to the

expense of a

beaver hat, being able to purchase one made a visual statement

about

one's wealth and social status.  In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, beaver hats

were produced

for sale domestically in the French and British markets, as

well as for

export. The French domestic market included

military and naval

contracts, as well as consumer products sold on the general

market. The majority of their exports were shipped to

French

colonies in the Caribbean, Italy, Portugal, Spain, and Spanish

South

America.[6]

Britain's exportation of beaver hats picked up in the

eighteenth

century, after the acquisition of much of the Hudson Bay

Territory of French

Canada following the War of Spanish succession In the

1720's, the

British exported to their own Caribbean colonies in Jamaica:

two dozen

beaver hats and one dozen half beaver hats); three dozen

half beavers

to Bilbao; three dozen beaver hats to Barbados; and three

dozen beaver

hats and three dozen felts to Calais. By the 1730's,

Britain "exported formerly by the dozens but now by the hundreds of

beaver and half beaver hats to the British West Indies."[7]

On the European continent, Britain was able to infiltrate the Iberian

market. From 1700 to 1750 the revenue from beaver hats shipped to

Spain and Portugal, and then on to their colonies, increased from

£44,000 to over £263,000.[8]

Of Britain's fur exports, 85% were comprised of beaver hats, 45%

of which were exchanged with Spain and Portugal for bullion.

Additional evidence regarding the sale of beaver hats in Europe

demonstrates greater English sales in Holland and Germany, with French

advantages in Switzerland, the Baltic, and smaller markets in Spain and

Italy.[9]

In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, beaver hats

were produced

for sale domestically in the French and British markets, as

well as for

export. The French domestic market included

military and naval

contracts, as well as consumer products sold on the general

market. The majority of their exports were shipped to

French

colonies in the Caribbean, Italy, Portugal, Spain, and Spanish

South

America.[6]

Britain's exportation of beaver hats picked up in the

eighteenth

century, after the acquisition of much of the Hudson Bay

Territory of French

Canada following the War of Spanish succession In the

1720's, the

British exported to their own Caribbean colonies in Jamaica:

two dozen

beaver hats and one dozen half beaver hats); three dozen

half beavers

to Bilbao; three dozen beaver hats to Barbados; and three

dozen beaver

hats and three dozen felts to Calais. By the 1730's,

Britain "exported formerly by the dozens but now by the hundreds of

beaver and half beaver hats to the British West Indies."[7]

On the European continent, Britain was able to infiltrate the Iberian

market. From 1700 to 1750 the revenue from beaver hats shipped to

Spain and Portugal, and then on to their colonies, increased from

£44,000 to over £263,000.[8]

Of Britain's fur exports, 85% were comprised of beaver hats, 45%

of which were exchanged with Spain and Portugal for bullion.

Additional evidence regarding the sale of beaver hats in Europe

demonstrates greater English sales in Holland and Germany, with French

advantages in Switzerland, the Baltic, and smaller markets in Spain and

Italy.[9]