The Late 1800s

By the 1850s, most of the world’s cotton was grown in the American south and spun and woven in the industrial cities of Northern England. Formerly prosperous areas of manufacture, especially India, faced trying economic times as weavers struggled to compete with cheap manufactured cloth. Meanwhile, the southern American planter elites tried to insure that the “peculiar institution” of slavery continued, despite growing abolitionist sentiment in the north and in Europe.

This system was totally disrupted by the American Civil War. The economic historian Sven Beckert brilliantly outlined this disruption, and the long-term changes in the global cotton industry, in an academic article published in 2004. Per Beckert, the American Civil War cut off the major global source of raw cotton all in one fell swoop, driving panicked industrialists in Britain and elsewhere to immediately seek out new areas of cotton production. Within a few short years, cotton production had absolutely exploded in regions attached to the European-dominated world economy; Brazilian cotton production doubled, Indian production quadrupled and Egyptian production quintupled. Likewise, cotton production grew in areas as diverse as parts of Central America and Central Asia. While the war lasted and cotton sold for a high price on the world market, there was a brief period of prosperity for many small farmers; British interests complained that Indian farmers were attaching silver wheels to their wagons – this was nonsense, of course, but it was true that Indian farmers enjoyed a few years of improved standards of living.

After the war ended in 1865, however, the conditions that had created those brief boom times collapsed. The concern on the part of the cotton manufacturers back in Britain (and, soon after, the United States) was how to secure low-cost raw cotton in the absence of slave labor. The solution was a new system of debt and coercion. In almost every one of the new producing regions, draconian labor laws were pushed through that tied sharecroppers and small farmers to the land, often through crop liens and chronic debt. In other words, banks and cotton merchants, usually affiliated with European capital, provided loans to small farmers, who used the money to purchase cotton seed and farming implements. In the post-Civil War global economy, prices for cotton varied considerably year to year, putting cotton-producers at the mercy of market fluctuations. During good years, they could cover their debts and perhaps make a small profit for themselves. For the most part, however, they were barely able to keep up with interest payments and often had to take further loans to survive.

A terrible global economic depression occurred in 1873, with dire consequences for cotton farmers. Areas like the cotton-producing regions of India that had so recently enjoyed the brief economic boom of the Civil War era were plunged into an abyss of poverty and, soon, famine. Where cotton farmers had once produced foodstuffs to supplement their cash crops, all available land had been converted to cotton production in the 1860s. As prices fell well below the level of sustainability, farmers simply starved. Not for the last time, India was the setting of a macabre scene in which locomotives loaded with grain rolled past the bodies of starving peasants. While the cotton industry eventually recovered from the depression, the pattern of cotton production by debt-laden sharecroppers and small farmers would remain the major “solution” to the labor problem that had been created by the end of slavery in the United States for decades to come. This was certainly the case in the United States itself – sharecropping and tenant farming locked many former slaves into patterns of life scarcely less difficult than slavery itself had been only a few years before.

Of course, by the time the late-nineteenth century pattern of sharecropping and debt peonage had emerged, the first stirrings of mechanization in harvesting were already stirring. The twentieth century would see the expansion of enormous cotton farms and the end of the small cotton farmer as a result.

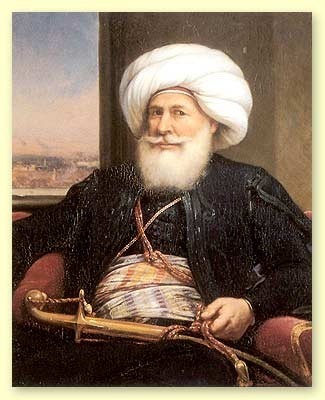

Mehmet (Muhammad) Ali of Egypt, who began the large-scale cultivation of cotton in Egypt in the 1820s. Egyptian cotton farming exploded after the beginning of the American Civil War in 1860.

Source:

Sven Beckert, “Emancipation and Empire: Reconstructing the Worldwide Web of Cotton Production in the Age of the American Civil War,” American Historical Review, Vol. 109, No. 5 (December 2004).