Bananas and Popular Culture

From its inception as a domesticated crop, the banana has played an important role in human culture. Humans have consumed the banana culturally as assuredly as they consume the banana as a food. In ancient civilizations, the banana held important roles in cultural traditions. In Peru, banana leaves’ presence in Incan tombs indicates a religious connection. Green bananas surrounding a green coconut was an important religious offering to Buddhists in Southeast Asia. Hawaiian legends refer to the plantains’ connection to the fabled Menehunes, a semi-mythical race native to the Hawaiian Isles. Bananas may also have reached saturation in many ancient languages, as current scholarship on the history of language notes the omnipresence of bananas in recorded languages throughout the tropics.

As the banana diffused across the tropical world, it became important in textile design and creation in many cultures. African societies used banana sap as a dye to stain patterns onto fabric, and made necklaces out of wild banana seeds. Thirteenth century Japan cultivated a particular banana for its fibers, which were processed into various weavings. The finest, softest fibers were used to line the insides of kimonos, and thus held a special place in Japanese culture.

As the banana gained importance as an export fruit, it simultaneously gained importance in the popular culture of Europe and America. From literature to music, bananas contributed to the development of popular culture, including, in some cases, becoming endowed with symbolic meanings. The burgeoning silent movie industry made liberal use of the supposed frictionless quality of the banana peel in countless instances of physical comedy. In 1929, William Faulkner featured a symbolic banana in his novel As I Lay Dying, and the banana musicians throughout the twentieth century appropriated the plantain for lyrical symbolism.

In 1923, Frank Silver and Irving Cohn released a song entitled “Yes, We Have No Bananas!” to great fanfare. Swing bands throughout the country appropriated the song to play at dance halls, and the sheet music for the song sold upwards of a thousand copies a day. Though the song’s popularity may have had more to do with its medley of popular song melodies rather than its reference to bananas, yet its use of the plantain heralded a century where the banana saturated both public marketplaces and popular culture. George Gershwin incorporated the banana into such compositions as “Let’s Call the Whole Thing Off” and “But Not for Me,” indicating the plantains successful colonization of American culture. In Britain in 1982, an all-girl pop group took the name “Bananarama,” which alluded to the style of one of their songs. Harry Belafonte’s popularized version of the “Banana Boat Song” was released on the first album to sell over a million copies, Belafonte’s Calypso. The suggestive shape of the banana itself led to an increasing association of the banana with sexual imagery and themes.

By the 1920s and 1930s, lyrics that included the banana often alluded to it as phallic symbol. “I’ve Never Seen a Straight Banana,” by the Happiness Boys, “Banana In Your Fruitbasket,” by Bo Carter, and Memphis Minnie’s “Banana Man Blues” all referenced the banana as a fruit of symbolic sexuality. In 1943, Busby Berkeley’s bizarre performance “The Lady in the Tutti-Frutti Hat” from The Gang’s All Here featured dancers riding gigantic banana and strawberry props as Carmen Miranda sang, to the shock of viewers everywhere. By the 1940s, the sexual images of the banana became increasingly associated with exoticized and racist images of the fruit, as the creation of the “Miss Chiquita” character for the United Fruit Company’s advertisements attests. Miranda herself often featured bananas prominently on stage, which formed connections between the fruit and her sensual dancing. Interestingly enough, the Miranda’s performances may have been calculated for an over-the-top quality that simultaneously celebrated the banana as a sex symbol while parodying it.

Less comic and more sinister connections of the banana to sexually racist images also appeared in American popular culture throughout the century. In his 1923 collected poems Harmonium, Wallace Stevens’ words from “Floral Decoration for Bananas,” depicts a disturbing mix of racist sexuality.

Well, nuncle, this plainly won’t do.

These insolent, linear peels

And sullen, hurricane shapes

Won’t do with your eglantine.

They require something serpentine.

Blunt yellow in such a room!

You should have had plums tonight,

In an eighteenth-century dish,

And pettifogging buds,

For the women of primrose and purl,

Each one in her decent curl.

Good God! What a precious light!

But bananas hacked and hunched…

The table was set by an ogre,

His eye on an outdoor gloom

And a stiff and noxious place.

Pile the bananas on planks.

The women will all be shanks

And bangles and slatted eyes.

And deck the bananas in leaves

Plucked from the Carib trees,

Fibrous and dangling down,

Oozing cantankerous maws,

Darting out of their purple craws

Their musky and tingling tongues.

(Wallace Stevens, “Floral Decoration for Bananas,

as accessed online at: http://www.101bananas.com/everything/

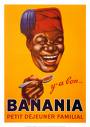

Darker yet was the association of bananas with racist images. Black players in Europe could expect to be assaulted with bananas and insults upon taking the field during soccer games. The French dessert product made of banana flour and cocoa “Banania” featured a highly caricatured image of a black man, replete with a pidgin phrase, to help sell the product. In Asian-American slang, a “banana” is an Asian-American who has become overly assimilated, and thus, outwardly “yellow” while inwardly “white.”

Upon its arrival in the United States and Britain, bananas rapidly formed an ubiquitous presence not only in the twentieth century marketplace, but also in popular culture. Phrases such as “Going Bananas,” “Banana Republics,” “Top Banana,” and “Banana Boat” were present as popular diction. From humor to racist and sexual images, the fruit has enjoyed popularity among comedians, musicians, politicians, and performers alike as evocative of various themes and memes. This trend continues on into contemporary society today, as illustrated by the “dancing banana” icon found widespread across the world wide web. The banana’s resonance as a cultural symbol is matched only by its popularity as a fruit and food.

Bibliography:

Anonymous, “Society Has to Change – Barnes.” BBC Sport: TV & Radio – World

world_football/2399629.stm; accessed on 10 June 2008.

Banana; accessed on 10 June 2008.

Banania; accessed on 10 June 2008.

Connor, Steve. “Lack of Sex Life Threatens Banana Crops.” The Independent, 27 July

2001.

Mirsky, Steve. “Attack on the Clones.” Scientific American vol. 298, no. 4 (March

2008).

Sharrock, Suzanne. Uses of Musa. Montpellier: International Network for the

Improvement of Banana and Plantain, Focus Paper III. INIBAP Annual Report

1996, 42-44.

Soluri, John. Banana Cultures: Agriculture, Consumption, and Environmental Change

in Honduras and the United States. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2005.

Soluri, John. “Banana Cultures: Linking the Production and Consumption of Export

Bananas, 1800-1980.” In Banana Wars: Power Production and History in the

Americas, ed. Steve Strffler and Mark Morberg, 48-79. Durham and London:

Duke University Press, 2003.

Stevens, Wallace. “Wallace Stevens, “Floral Decoration for a Banana,” as accessed on:

Wiley, James. The Banana: Empires, Trade Wars, and Globalization. Lincoln:

University of Nebraska Press, 2008.

Bananas and Popular Culture